Beading, Technology, and the Art of Barry Ace

The Importance of Beading

In order to understand beading as a technology, it is necessary first to have an understanding of the historical importance of traditional beadwork.

Beading has always been a very important element of the culture of Indigenous Peoples in what is now Canada and the United States. Some beadwork was made to be traded at trading posts, while some was made for ceremony or special events. Prior to contact, Indigenous people would bead with materials found on the land, such as shell, bone, pearl and stone. It wasn’t until after European settlers arrived that more modern, brightly coloured materials such as glass and ceramic came into use.

Beadwork played a significant role in the inception of “Canada,” especially in formalizing the agreements between Indigenous nations and European settlers. Many original treaty agreements were solidified in beaded Wampum Belts such as the Two Row Wampum and the 1794 Canandaigua Treaty Belt.

Although Wampum Belts are widely known for their role in the creation of treaties, traditionally, they were used for many purposes, such as nation-to-nation meeting requests, symbols of titles within communities, and during ceremonies, to name just a few. Wampum are held in extremely high esteem by Indigenous communities, particularly the Haudenosaunee. They carry important responsibilities that must be honoured by those who walk with them.

Wampum beads are especially significant because they are made from quahog and white whelk clamshells, and are therefore considered a living record. When creating a Wampum Belt, the maker intentionally speaks their words into the beads. This allows each speaker thereafter to remember the original agreement and the history to date, and they are expected to honour the original words.

Barry Ace: Beading in the 21st Century

Barry Ace is pushing the boundaries of traditional beadwork and is connecting tradition with innovation in the 21st century. He is Odawa Anishinaabe from M’Chigeeng First Nation on Manitoulin Island, lives in Ottawa, and has been an artist for 25 years.

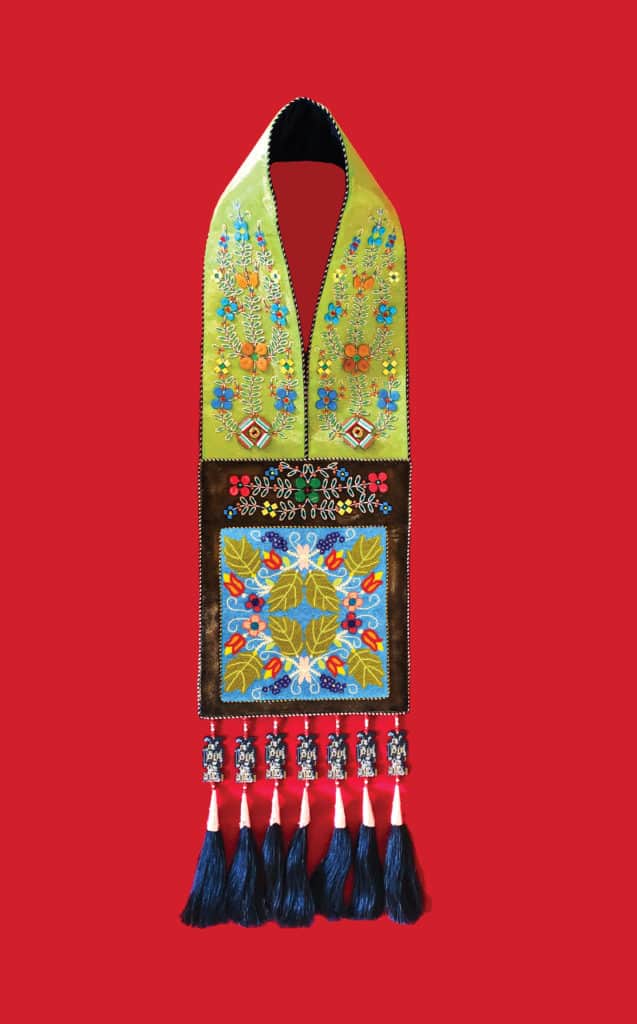

Ace uses reclaimed and salvaged electronic components and circuitry to create traditional woodland-style beadwork on important items of Anishinaabeg regalia, such as the Bandolier Bag. He creates this artwork to show that Indigenous culture has never been static; it is always evolving, and Indigenous peoples are always looking for new forms of cultural expression. According to Ace, traditional beadwork and technology have a relationship, as is reflected in the Anishinaabemowin language. Manidoomin—the word for “bead”—translates to “spirit berry” which is known to give power; therefore, dancing in regalia releases power to the community. This is similar to electronic circuits, whose components store energy, which they release when a drop in external energy is detected, thereby increasing the supply.

Ace’s work is a brilliant example of the way cultural evolution has always taken place. Too often, Indigenous communities, traditions, cultural practices and ways of knowing are misunderstood as “outdated” for modern times, and are therefore considered to be unimportant or invalid.

Ace’s work connects traditional knowledge and practices to contemporary technology, which provides a powerful statement about the resilience of Indigenous communities.

His artwork exemplifies the strength required not only to learn traditional knowledge that was taken from Indigenous Peoples, but also to use that knowledge in contemporary ways, to continue building for future generations. Ace’s artwork is a beautiful representation of the limitless innovation of Indigenous people and communities when they are given equal opportunities to learn science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics.

Beading + Technology

In recent years, Indigenous communities have seen a resurgence of beading that is directly related to the use of technology. Opportunities for Indigenous people from all over Turtle Island to connect and learn from each other has dramatically increased because of modern communication technology. Increased access to shared cultural knowledge, community support, and traditional art forms has had a positive impact on the lives of countless Indigenous individuals.

Social media, online streaming platforms, video platforms and apps have been particularly important to the resurgence of beading. Apart from providing access to skills and patterns, they have been used to create welcoming, open and supportive online communities where individuals can easily share cultural knowledge and tips, and ask questions without fear of judgment.

Communities are created through online interactions on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube, and contribute to the success of Indigenous people personally, professionally and economically. Technology has allowed more Indigenous artisans to market, sell and trade their work, as well as to support and celebrate other Indigenous artisans. These online communities also encourage the next generations to find power in traditional Indigenous art forms such as beadwork.

For many Indigenous people, beading is seen as a medicine in itself; it is a deeply healing ceremonial practice that has the ability to connect individuals to their ancestral roots. Learning the traditional art form of beading is an act of resistance against the historic and ongoing oppression experienced by generations of Indigenous people in this country. This act of resistance is an extremely powerful example of cultural revitalization, identity re-formation, personal and community healing, diversity, resilience, and communal strength among Indigenous communities.

To learn more, visit the Onondaga Nation website.

Online Tools for Beading

Beading apps / websites for pattern making:

Free digital art software for freehand pattern creation: